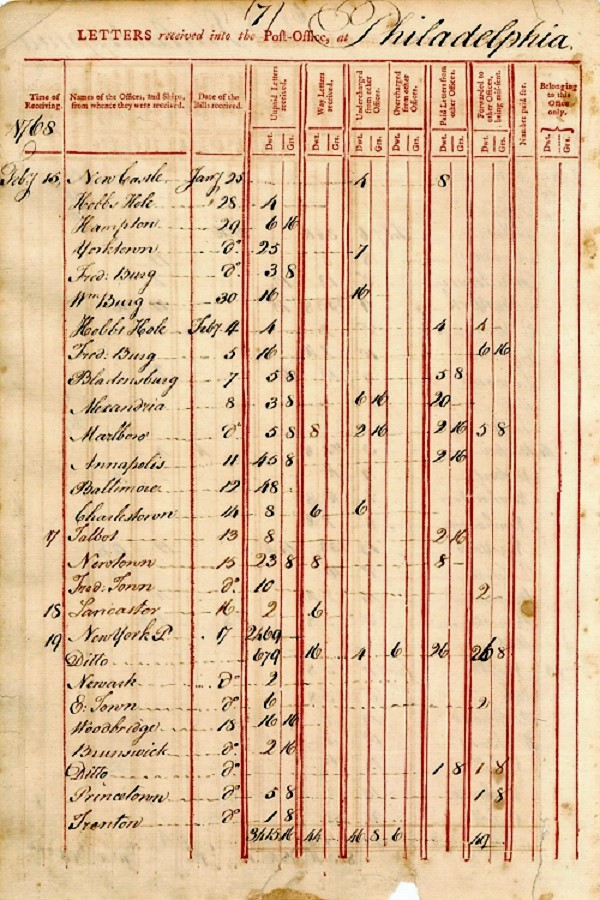

Postmaster General Benjamin Franklin’s ledger from Feb. 15, 1768, offers data about the mail going in and out of the Philadelphia Post Office.

The ledgers that Benjamin Franklin kept when he was Philadelphia’s Postmaster recently became available online — in time for this weekend’s 245th anniversary of the American postal system’s birth.

Franklin became America’s first Postmaster General 245 years ago when he was appointed to that position by the Second Continental Congress on July 26, 1775.

Prior to that appointment, Franklin had been Deputy Postmaster General of British North America — named to that position by agents of King George II in 1753 after having served as the British Crown Post’s Postmaster in Philadelphia since 1737.

“Curiously, despite his involvement of nearly 40 years [with the early American postal system], this aspect of Franklin’s civic engagement has been the subject of little study in comparison with his other achievements,” according to the American Philosophical Society, which recently posted Franklin’s ledgers on its website.

The society, which was co-founded by Franklin in 1743, has possession of many of his letters, notes and account books.

Visitors to the society’s website can see and download images of Franklin’s postal ledgers as well as read about what the ledgers contain and their historical context and significance.

While the ledgers don’t appear to give insight into Franklin’s day-to-day routine, they do contain plenty of data about the mail going in and out of the Philadelphia Post Office.

For example, the ledgers show that John Mifflin was the recipient of the most mail between 1748 and 1752. The successful Quaker merchant received 708 letters and packets, with 628 coming from Boston, 57 from New York, 19 from Rhode Island and three from Virginia.

They also show that mail from New York and Boston made up the bulk of the incoming mail into the Philadelphia Post Office while mail from the southern Colonies rarely made an appearance.

Stephen Kochersperger, a senior research analyst in postal history at USPS headquarters in Washington, DC, spent some time earlier this year examining the ledgers.

“What struck me was how much work they had put into scanning them to produce such high-quality images,” he said. “A lot of these images are really difficult to read because they are in cursive and the ink is faded.”

The style of cursive writing in that era, Kochersperger notes, is different from today’s cursive. For example, the letter “s” is often rendered to look like the letter “f.”

“But the Philosophical Society is having the ledgers transcribed, so they have data sets for some of these ledgers, which is the most impressive feature of the digital collection,” he said.

Source: USPS