By Editorial Board – January 26, 2016

By Editorial Board – January 26, 2016

THE SENATE could not have chosen a more appropriate title for last week’s committee hearing on the nation’s troubled postal system: “Laying Out the Reality of the United States Postal Service.” Witness after expert witness explained just how desperate that reality is. In the age of email and text messaging, first-class mail, the Postal Service’s most profitable product, is in terminal decline: down 35 percent over the past decade, according to Megan J. Brennan, the postmaster general. Package delivery, though growing, is less profitable per piece and not nearly enough to offset the death of first-class. The result, according to James E. Millstein, a former Obama administration Treasury Department official who helped government-led restructurings of AIG and Ally Financial: If the Postal Service were a private company, “it would undoubtedly be viewed as insolvent.”

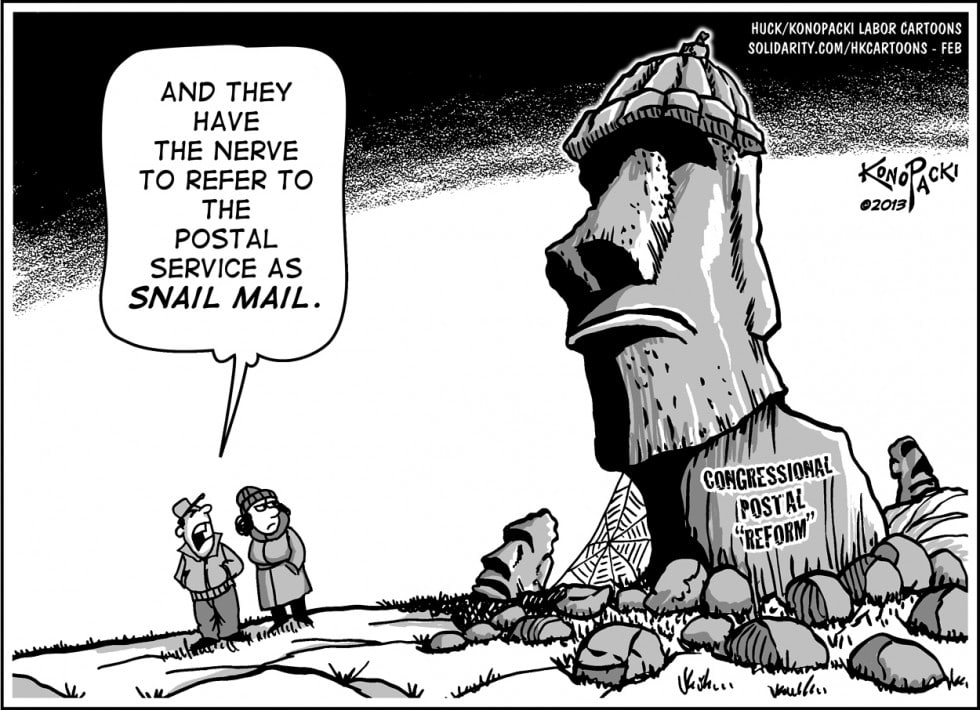

Grim as these financial facts were, the most depressing reality to come out of the hearing was a political one: Fundamental postal reform is moribund.

Yes, “stakeholders” represented at the hearing — postal unions, USPS management, paper producers, mailers — testified in favor of a bill that would accomplish two important objectives. It would modify the current onerous annual requirement to pre-fund several billion dollars’ worth of postal retiree health benefits and shift Postal Service retirees from a separate plan onto Medicare, which they already support with payroll taxes. And it would extend a two-year-old 4.3 percent “exigent” postal rate increase that’s set to expire in April. Letting it lapse would cost the USPS $2 billion per year.

Yes, “stakeholders” represented at the hearing — postal unions, USPS management, paper producers, mailers — testified in favor of a bill that would accomplish two important objectives. It would modify the current onerous annual requirement to pre-fund several billion dollars’ worth of postal retiree health benefits and shift Postal Service retirees from a separate plan onto Medicare, which they already support with payroll taxes. And it would extend a two-year-old 4.3 percent “exigent” postal rate increase that’s set to expire in April. Letting it lapse would cost the USPS $2 billion per year.

But this measure represents the political lowest common denominator, the bare minimum to keep the Postal Service afloat — and not the structural changes needed to ensure long-term viability. Gone are previously contemplated reforms such as right-sizing the Postal Service’s network of distribution centers or requiring labor arbitrators to factor in the USPS’s financial woes when deciding on new pay and benefits. Reformers have capitulated on five-day delivery for letters, even though two-thirds of the public would be willing to sacrifice Saturday mail, according to a 2015 survey by the Program for Public Consultation at the University of Maryland’s School of Public Policy. No one is even talking about the obsolete regulatory structure that ties down the USPS like Gulliver among the Lilliputians. Instead, “reform” has been defined down to include such cash-generating gimmicks as shipping beer and wine through the mail.

Behind this failure of democratic governance are the aforementioned “stakeholders” — or, to be more precise, the deference they get from Congress, which responds to their lobbying on behalf of various parts of the existing system that advantage them rather than to the public’s interest in a modernized, financially sound USPS. “As much as we try to have an elevated conversation about the future of the organization,” 40-year Postal Service veteran Patrick R. Donahoe said upon his retirement as postmaster general a year ago, “we never get beyond the narrow set of interests that are determined to preserve the status quo.” If the United States’ once-proud postal system does someday succumb, those words could serve as its epitaph.